Posts on topical issues in clinical and public healthcare policy

from the snowcapped mountains of Singapore

Rebalancing Healthcare Services and the "Capability Trap": A Systems View

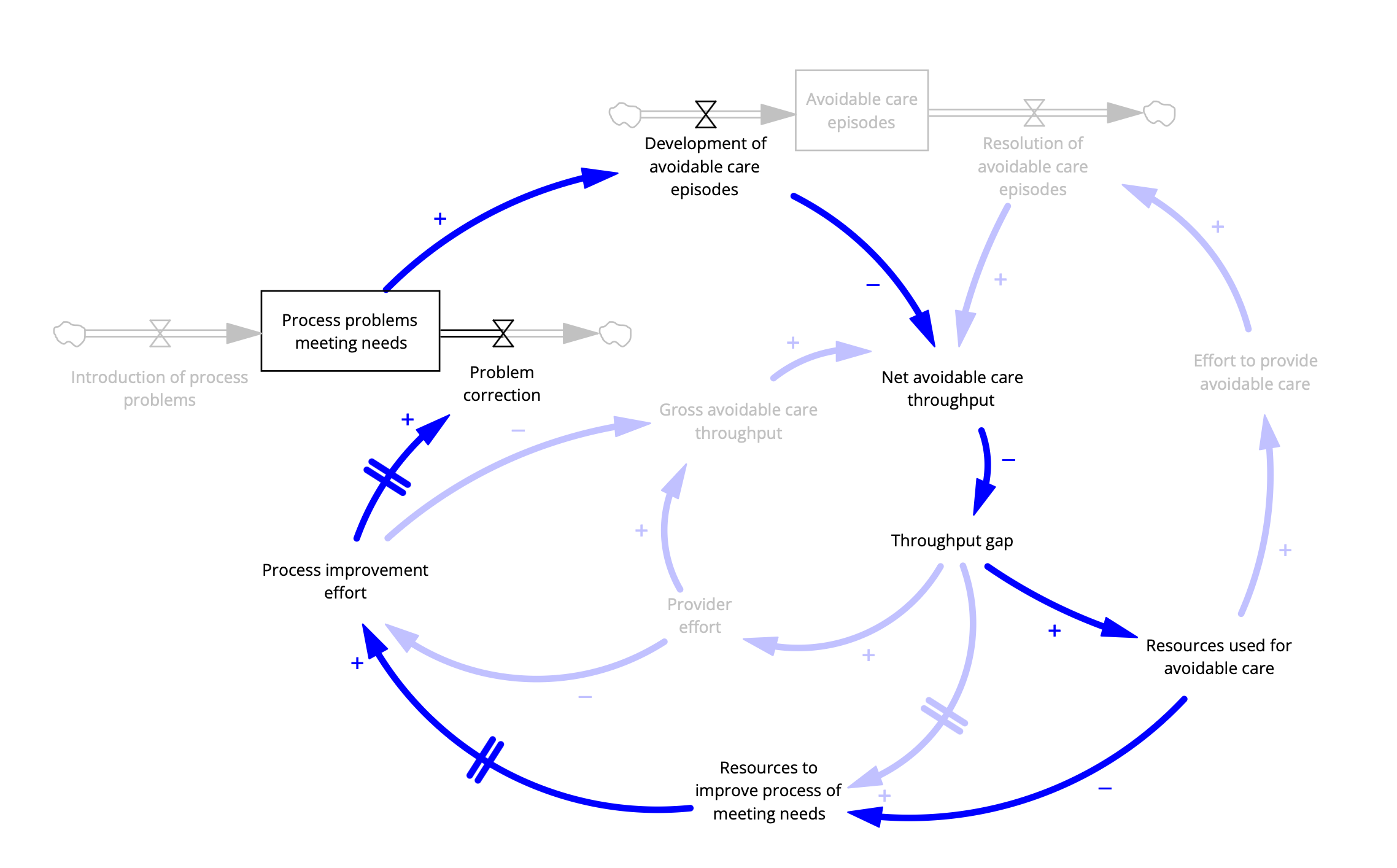

The capability trap applied to healthcare. Based on Sterman, 2002, thanks to Prof. Peter Hovmand, Case-Western.

This brief post provides an example of a systems thinking method used in System Dynamics, the Stock and Flow Diagram. Here it’s applied to the phenomenon described in my last post, “sizzle then fizzle” (innovation that fails before it has a chance to succeed), also known as the “capability trap”.

With populations aging rapidly and the associated increase in complexity of health and social care needs, the necessity of rebalancing healthcare resources towards primary and community care is undeniable. To effectively manage these emerging health demands, services must become better coordinated, with greater emphasis on preventive care, palliation, and community-based interventions. Indeed, our research team has demonstrated through simulation experiments that enhancing primary and community care can significantly reduce unnecessary hospitalizations, improve health outcomes, and extend healthy life expectancy.

Yet despite these clear benefits, meaningful rebalancing remains elusive.

What we see today is growing recognition of the value of an accountable point-of-care—typically a primary care physician (PCP)—who identifies, meets, or coordinates patient needs through onsite care or timely referrals to other providers. A robust primary care system would integrate preventive care, acute care management, chronic disease control, mental health services, and social determinants of health into a cohesive, patient-focused strategy. However, as emphasized in previous discussions, the current structure and staffing of most primary care practices simply cannot meet these comprehensive demands. In short, PCPs face overwhelming workloads without sufficient capacity, resources, or coordination support.

Given this reality, why not invest more substantially in primary care infrastructure? Why not significantly raise PCP compensation—which currently trails far behind that of specialists—to incentivize careers in primary care? Why not expand primary care teams by integrating non-physician clinicians who can deliver standardized, guideline-based care and free PCPs to handle more complex issues? Furthermore, why not develop comprehensive, integrated medical records that bridge medical and community services to ensure coordinated, continuous patient-centered care?

Several factors contribute to this inertia. In the context of a broad range of improvement programs, both public and private, management theorists suggest that it could be behavioral bias (specialty and hospital services are much cooler than dull as dishwater primary care services). It may be that policy makers disbelieve the benefits to whole system performance (if primary care was that good it would have already been prioritized) or it could be lack of capital (I’d like to invest in primary care, but if we have cash, we need to use it for urgent short-term needs).

However, another powerful systemic barrier—often overlooked—is the phenomenon known as the "capability trap", a term coined by systems thinker John Sterman. The capability trap arises when organizations consistently divert resources from building long-term capabilities (such as preventive and community-based care needs) to address immediate performance pressures (like acute hospital demands). Over time, this short-term reactive cycle erodes the very capabilities needed to achieve long-term performance, creating a reinforcing feedback loop that entrenches chronic underinvestment in foundational services.

A more detailed description of the feedback loops involved at the end of this post.

In healthcare, this trap manifests clearly: hospitals and specialist services, facing urgent short-term pressures, attract resources away from primary and community care investments. The weaker primary care becomes, the greater the demand on specialist and acute care services—perpetuating the cycle. Breaking free of this capability trap requires intentional, sustained investment in primary care infrastructure, workforce development, and service coordination despite immediate pressures.

A systems perspective thus clearly reveals the necessity—and the difficulty—of rebalancing healthcare. Making this shift requires not only recognizing the long-term value of primary and community care but also systematically addressing and disrupting the reinforcing feedback loops that underpin the capability trap itself.

The Stock and Flow diagram shown here again represents a dynamic causal hypothesis in which the “capability trap” theory is applied to healthcare.

Notation

Boxes represent measurable features of the system that accumulate and diminish over time (like water in a bathtub).

Double arrows with a “valve” are flows into and out of stocks (like faucets and drains). These flows are influenced by features that change over time and the single arrows represent causal statements: the entity at the tail of the arrow causes an increase or decrease in the entity at the arrowhead, all other things being unchanged.

The polarity of the relationship is reflected by a “+” or “-” sign adjacent to the arrow. If the sign is “+” then if the entity at the arrow tail increases then the entity at the arrow head increases (again ceteris paribus, for you Latin lovers).

Many of the arrows together form loops, such that one can start at one entity and follow a trail of arrows back to the same entity. These loops can be reinforcing loops (that is, an increase in the entity is further enhanced by the cause and effect chain of the loop. Or they can be inhibiting loops (or balancing) in that the loop’s effect is to suppress further increases in the entity.

Finally, arrows crossed by a double line in the middle denote that the effect has a delay.

Simplifying assumptions. The basic notion is that a well-functioning healthcare system identifies and meets needs that reduce the risk of avoidable healthcare problems. These problems are manifest as avoidable episodes of care (what would be considered a “defect” in the manufacturing context).

Reviewing the salient loops

With regard to the capability trap, there are several relevant loops. The simplest to see is at the right of the diagram.

The Rework Loop

The “Rework Loop” represents the effort that must be applied to address an avoidable episode such as a rehospitalization that occurs as a result of early discharge to a primary care provider without the capability to manage post-acute care. Starting with “Net avoidable care throughput” (the difference between the development and resolution of avoidable care episodes), when that is bad (low) the loop dynamic creates a balancing effect: low throughput leads to an increase in performance gap leads which leads to and increased allocation of resources to those immediate problems and greater effort to provide care, more rapid resolution of episodes and increase in net avoidable care throughput. This is the same dynamic that applies to manufacture rework of defects, or attention to bailing rather than repairing when faced with a leaking boat.

A similarly short loop is the “Working Harder” loop in which higher expectations are not matched by greater resources:

The Work Harder Loop

Here, in response to a reduction in net avoidable care throughput (that is there are an excess of avoidable care episodes such as those due to failure to meet mental health needs), the perceived gap is addressed by increasing provider effort: increasing care slots by reducing appointment length or extending hours, and so on. This will lead to increased throughput, but at a cost to provider satisfaction.

Now the more complex loops that relate to the capability trap: Focus on the loops that include “Development of avoidable care episodes”.

The loop we’d like to have is the one that will tend to reduce that rate, and thus alleviate the need for rework (with resources) or working harder (without new resources):

The Working Smarter Loop

In this balancing loop, “Working Smarter” an increase in the rate of avoidable care episodes reduces net throughput. In response to the resulting gap, resources are allocated to improve care process, which leads to greater effort to make fundamental process improvements, leading to an increase in rate of process problem correction, fewer unmet needs and ultimately fewer episodes of avoidable care episodes.

Nice.

But notice that there are 3 causal arrows with delays, which means that this “Working Smarter” loop takes time: time to allocate resources, to initiate concrete efforts and for those efforts to bear fruit.

In the meantime, there is another loop that is working against process improvement efforts.

The Competition Between Short- and Long-term Needs Loop

Follow the loops and the problem becomes apparent: more avoidable care episodes requires a response by administrators to allocate more resources to address the urgent problem.

Note that there are several other loops that influence the effort to broadly improve health system performance. Indeed, there are 6. I leave these to the reader to discover.

It's the System, Stupid

For the record, this phrase is a variation of James Carville's famous quote during the Clinton campaign, "It's the economy, stupid," which highlighted how voters' financial well-being determines elections. It's a call to recognize when we're focusing on peripheral issues while ignoring the elephant in the room.

I'm appropriating this phrase for healthcare because over my four decades in medicine and health services research, I've watched countless solutions target our dysfunctional healthcare system while avoiding the most obvious issue: the system itself. And by "system," I don't mean individual components like primary care practices or emergency rooms—I mean the entire interconnected structure. The whole ball of wax is the elephant in the room.

Several "movements" in Health Services Research have emerged to address healthcare's recognized problems of high cost, variable quality, limited access, and growing dissatisfaction among patients and staff:

The Outcomes Measurement movement (treating healthcare as an organism lacking a nervous system)

Total Quality Management movement (eliminating waste in specific care processes)

Evidence-based Medicine movement (only performing and paying for scientifically supported activities)

Population Health movement (addressing upstream prevention rather than downstream illness)

Shared Decision Making movement (engaging patients and families in informed choices)

Real-world Evidence movement (using electronic data and quasi-experimental designs to determine risk, efficacy, and cost)

Implementation Science movement (identifying solutions through mixed methods while deeply engaging patients)

Each approach legitimately identifies both a problem and a solution. But none—except perhaps Implementation Science—addresses the system holistically or tackles healthcare's emergent complexity. By "emergent complexity," I mean more than just having numerous parts (like an airplane) or uncountable components (like Earth's atmosphere). I'm referring to dynamic complexity where relationships constantly change, creating feedback loops and time delays that produce unintended outcomes. Each movement speaks to a truth, but each remains incomplete and has achieved limited success in addressing fundamental dysfunction.

One could blame this lack of success—evident in how these movements rise and fall in scientific and popular literature—on meager funding for health services research, which represents a tiny fraction of healthcare expenditures. Some might argue that with adequate resources, movements like outcomes research could have significantly improved cost, quality, and satisfaction.

I propose that while all these movements matter, they must be considered within the context of the system's full complexity—including payment structures, capacity, demand, information flows, epidemiology, and governance. We need a system change approach that goes beyond sentiment and matches the challenge. Specifically, we need an approach that engages stakeholders in healthcare processes and outcomes, operates from a shared causal framework to target promising leverage points, and enables decisions that stakeholders can truly own and advocate for, even if not perfectly optimal.

"Systems thinking" must be more than just an idea—it requires coherent methodology. Several approaches offer suitable foundations for complex systems improvement, including Theory of Constraints, Viable Systems Modeling, and System Dynamics. However, implementing these methods effectively requires overcoming significant hurdles: we need skilled practitioners who can engage diverse stakeholders, bridge content and methods, commit sufficient time and energy, and secure supportive leadership and resources.

Translating systems thinking from concept to measurable, sustainable change isn't easy. Currently, only a handful of people can support major initiatives in large health systems. This bottleneck must be addressed if we hope to avoid the "sizzle and fizzle" cycle that has characterized health services research history.

Let's not be stupid.

Healing the World: Using Systems Thinking to Promote Positive Change

We live in a wonderful, complex, and often damaged world. Maintaining viability and repairing damage is humanity's highest calling. This endeavor demands decision-making processes that are robust enough to meet these challenges. One of the central hurdles in fostering effective decision-making capabilities is the fundamental need for all stakeholders to take on a satisfying role in a socially robust process.

Among the various participatory decision-making methodologies, System Dynamics (SD) stands out as a prime example of "systems thinking" tools designed to fulfill this need. With a well-established theoretical foundation, SD aims to model the feedback dynamics of real-world problems in a visually accessible format. It allows for the testing of alternative policies, enabling stakeholders to explore potential impacts of their decisions in a structured manner.

However, the journey to effectively learning and applying System Dynamics is not trivial. While graduate programs can impart the principles of Group Model Building and the essential concepts of feedback loops and system behavior, practical application requires more than just theoretical knowledge. Successfully finding the “requisite” model to address specific issues—one that is no more complicated than necessary—demands a nuanced understanding of both the problem and the audience.

Importantly, systems thinking is very different from technical optimization. The central goal of SD is to advance informed decision-making; we are not creating “technocratic elites” to make decisions for others. An effective practitioner engages in careful problem framing, leveraging insights from content experts and on-the-ground stakeholders while fostering inter-community bridges.

Newly minted graduates, especially those who have completed only a foundational course, often find themselves at a disadvantage. Without a strong mentoring environment, they may struggle to translate their academic learning into practice. This gap can lead to poor application of SD principles or, worse, a complete abandonment of the approach altogether. As a result, the potential of systems thinking to foster meaningful participation and informed decision-making may go unrealized, ultimately hindering our collective ability to address complex challenges in our world.

In applying System Dynamics, practitioners frequently encounter several common mistakes that can undermine the effectiveness of their models and decision-making processes:

Overcomplicating Models: New practitioners often create overly complex models that are hard to understand and communicate.

Neglecting Stakeholder Involvement: Failing to involve relevant stakeholders can lead to a lack of buy-in and critical insights.

Ignoring Data Limitations: Relying on incomplete or poor-quality data can yield misleading results.

Assuming Linear Relationships: Mistaking complex relationships for linear ones can oversimplify system dynamics.

Underestimating Feedback Loops: Overlooking the significance of feedback loops can result in an incomplete understanding of system behavior.

Lack of Sensitivity Analysis: Not assessing how changes in key parameters affect outcomes can lead to overconfidence in predictions.

Inadequate Iteration: Treating the model as a one-time project rather than an iterative process can hinder its development.

Poor Communication: Presenting results without clear strategies can alienate stakeholders.

Focusing Solely on Quantitative Outcomes: Neglecting qualitative factors leads to an incomplete understanding of the system.

Lack of Clear Purpose: Entering the modeling process without defined objectives can result in aimless efforts.

By being aware of these challenges and common mistakes, practitioners can enhance their application of System Dynamics, leading to more effective decision-making and a greater impact on complex challenges. In the end, the pursuit of systems thinking not only enriches our understanding but also fosters collaborative efforts toward meaningful solutions.

But real healing requires more than charming sentiment or technical competence.

A Modern Healthcare System: From Producing Services to Producing Met Needs

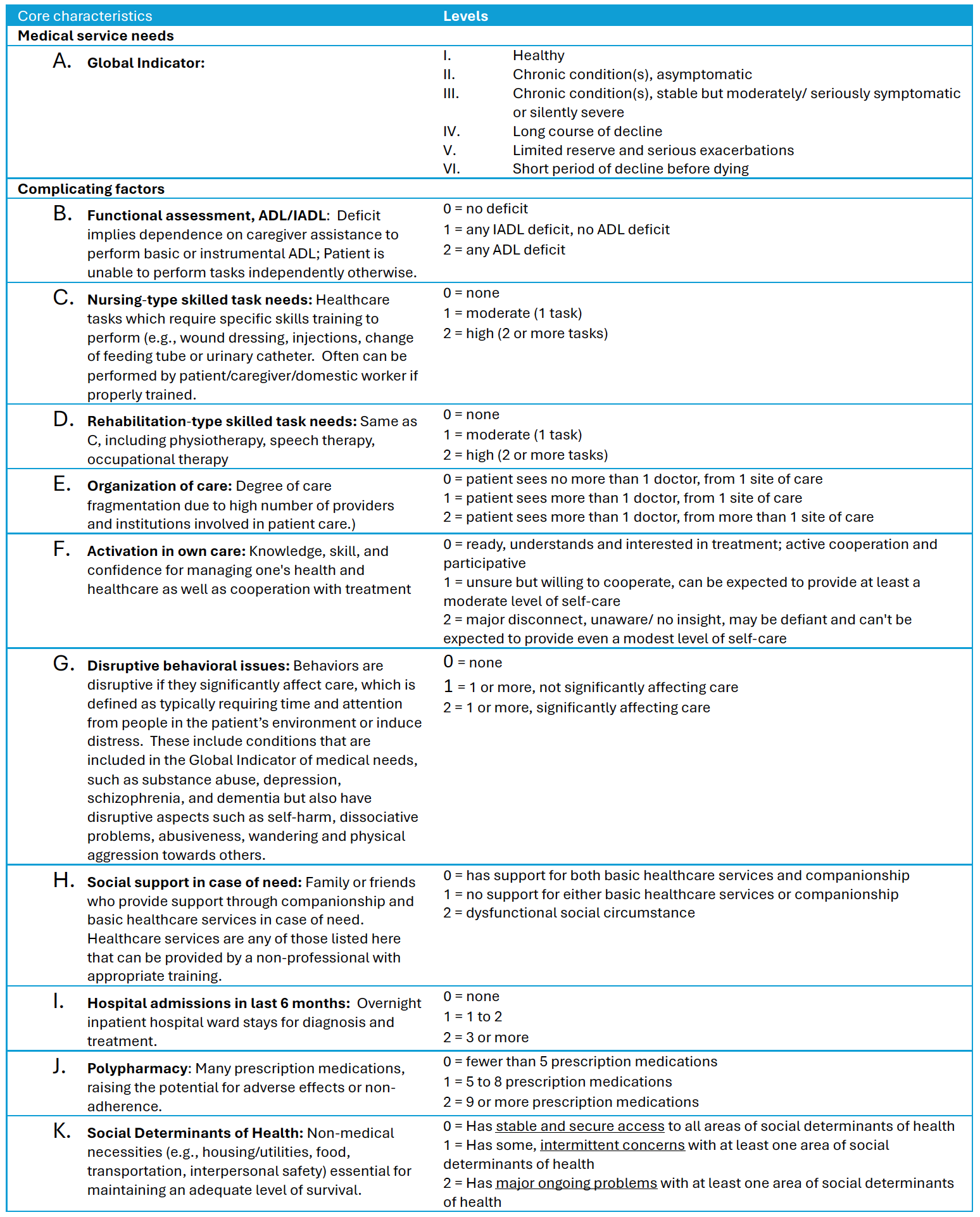

The conceptual foundation for a practical population segmentation measure based on functional service needs. Adapted from Lynn, et al,

Healthcare has evolved dramatically over the past century. While we've seen remarkable advances in treatments and technologies, we've also witnessed the rise of an impersonal, fragmented, and increasingly expensive system. To address these challenges, we need to fundamentally reframe – in practical terms – our approach to improving healthcare delivery.

In my previous blog, I suggested a crucial part of the solution is changing our fundamental unit of health system production to "meeting needs" – a patient-centered approach that aligns with the complexities of modern healthcare.

Traditionally, an accountable individual – typically a General Practitioner, Family Practitioner, General Internist or General Pediatrician – “provided services” and “met needs” that were one and the same. However, as the world has become more complex, we have tended to propagate piecemeal solutions all with the same structure and in many ways, the health system has gotten worse. In system thinking terms, our focus on providing more and more types of services constitutes a “fixes that fail” dynamic. Tangible examples of system failure include:

· Fragmentation: The rise of specialization has eroded the role of primary care providers as leaders of patient care, resulting in gaps in accountability and communication. With multiple “service production islands”, in practice everyone is accountable, which means that no one is accountable.

· Cost inflation: With services as the unit of production, it is only natural that payment is based on the provision of services, that is fee-for-service. Fee-for-service incentivizes quantity of services. The advent of insurance payment based on services adds fuel to the fire.

· Proliferation of low value services with high margins. Fee-for-service payment based on units of service incentivizes quantity of high-margin (i.e., profit or surplus generating) services. Often the services with the highest margin are not the services that are likely to most positively impact future life course.

· Patient confusion: Patients often request suboptimal services due to misinformation, or self-serving marketers.

We propose a practical solution that addresses these issues by changing the measure of health system production from “units of services” to "units of met needs".

So, let’s dig into what a transition to a needs-driven metric of production means in concept and in practice.

The "Meeting Needs" Approach:

What does a need-based unit of production even mean?

Conceptually, measuring healthcare system production as "units of met needs" follows 5 overarching principles:

1. Focus on needs that meet the relatively high bar of evidence or strongly held expert opinion that meeting a specific need has a high likelihood of optimizing health and, to the conversely, failing to meet needs is highly likely to lead to worsening.

2. Define health-related needs functionally, based on what successfully fulfilling the need looks like for the patient.

3. Use a simple classification system to identify typical sets of needs for different patient groups.

4. Identify patients with specific needs using a parsimonious list of characteristics. As a test of importance, each characteristic in our list would typically be included in a brief transfer discussion or note intended to communicate information that allows the receiving provider to deliver seamless care, making them aware of potential “bumps” in the care road. A corollary is that if the provider was not aware of a characteristic in the list, in order to provide adequate care, they should become aware.

5. Align with the goals of a "learning health system" that is intelligible by both clinicians and administrators, allowing coherent conversation and effective governance.

Our research team at Duke-NUS, Singapore has developed a needs-based segmentation too, the Simple Segmentation Tool© (SST) that follows the principles described here. In early development, the SST has demonstrated high interrater reliability in clinic settings and validity in emergency room patients, inpatient, and outpatients. Three versions of the SST are available: clinical (for the provider), survey (for the patient or a community surveyor), and national data versions (for national policy makers) are available. Each is in ongoing development and we welcome community involvement to pilot this instrument in clinical, community, and policy settings (See: https://www.duke-nus.edu.sg/hssr/simple-segmentation-tool).

What follows is a brief of how meeting needs as a measure of healthcare production works in concrete terms.

What is a “Need”?

A need, for our purposes, is anything that is necessary to achieve some objective; the primary objective of a healthcare system, is health. Now, in medical school, I learned about Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs in which the potential list of human needs could include anything from oxygen to transcendence. Certainly, oxygen and, arguably, transcendence could be considered needs that are in the purview of the healthcare system, but for current purposes, let’s consider a practical perspective: a health-related need is one that if met reduces the risk of progressing to more adverse health states that restrict engaging in life activities. As a foundation, we started with a list of health states adapted from the work by Lynn, et al. (2008) on “Bridges to Health” framework, along with a general set of needs:

Table 1. Health State and exemplar needs

Bridges to Health provides a general roadmap. To be useful, we need a bit more detail on needs.

[By the way, to those who favor Maslow’s need set as an aspirational goal for the healthcare system, I will not argue the point. We need to start somewhere we have problems and while optimizing health alone doesn’t assure Maslow’s self-actualization i.e., becoming the most that one can be, it at least provides for a level playing field in which that can happen.]

This raises a key operational question: What need relevant to the healthcare system should be considered in a core metric? Here we follow 3 principles to identify a core need.

1. To be considered a health need, we include activities within the span of control by the healthcare enterprise.

2. Amongst those “possible needs” we further restrict (as noted above) the operational list of need to those meeting a high bar – highly likely to have a salutary effect on health.

3. In the spirit of avoiding making the perfect the enemy of the good, consider the span to include activities that fulfill a range of health (i.e., medical) and health-related social service needs consistent with what the system already does (though perhaps not as well as we would like). Add a few extra elements that may not be traditional but strongly influence health and the ability of providers to successfully meet medical needs (e.g., addressing social determinants such as housing insecurity, food insecurity, as well as interpersonal violence which is a major influence on health and service utilization).

How does a “needs-based” metric deviate from a measure of “service-based” production?

In a service production system, needs are met if the means of service (a doctor visit, a home care worker, and so on) is intended to fulfill the need. In a met needs production system, needs are met if the means of service actually fulfills the patient’s need. This does not mean that the means of providing services is not relevant to whether needs are assessed as being met since some needs can only be fulfilled by someone with training, registration, and liability coverage. But the distinction between intention and actual fulfillment remains and has 2 profound implications.

· Simply engaging a means (i.e., a service) on behalf of a patient is not included in our measure of production, only the intended needs the service fulfills.

· Needs are open to be fulfilled by any means suitable to the resources and constraints of the system, providers, patient, family, and community, as long as they do fulfill the need.

The key to a practically operational needs-based health system is to de-conflate needs from specific service means. This is a challenge as, traditionally, meeting needs is linked directly to a particular service means (e.g., a home nurse, a physician). In the current framework, a need is linked to a function that when performed as intended will meet needs (and, in turn, reduce the risk of progressing to more adverse health states that restrict engaging in life activities). These functions are defined in terms of what constitutes success.

An illustrative list of needs and associated functions

Below is an example of health and health-related service needs in terms of the functions they are intended to fulfil.

Health needs aimed at optimizing physiological and psychological health include prevention based on age and gender (e.g., vaccination, screening for risk factors and early asymptomatic conditions, falls risk), primary care for common acute and chronic conditions (both physical and psychological), and specialty referral for alleviation of the effects of advanced or rare conditions, and special procedures).

Health-related service needs would relate to patient features that can complicate managing the health condition, including difficulty with activities of daily living, social isolation, polypharmacy, unobserved physiologic changes such as weight gain with heart failure, disruptive behavioral features and so on.

Functions are “means agnostic”, that is each function is defined in terms of what it looks like if the patient had that function successfully fulfilled: all prevention goals met, physiological parameters at prescribed targets, no difficulties with ADLs, not experiencing loneliness, on a core list of medications that are being taken consistently, in a safe and supportive environment, and so on. In our work with the SST, about 16 success-defined functions covers what the health system does (or could do) to optimize health.

Table 2. Service Functions

Classifying patients into segments with functions that needs to be met

For a useful metric for met needs, we identify a core set of patient features that individually or in combination typically correspond to one or more needs in our list. While this can get quite granular; for the purpose of flagging who might have a particular need or set of needs, in the SST the current list of patient features is limited to 11 core characteristics:

Table 3. Core patient characteristics

Pulling this together in a practical setting: a primary care practice in a regional health system

Imagine a large primary care practice embedded in a regional health system, serving a diverse urban population. Instead of focusing solely on the number of patients seen or services provided, the practice with its regional administrators adopt a consistent "meeting needs" approach. As an exemplar patient, consider a 70-year-old man with multiple chronic medical problems, including heart failure which has led to multiple recent hospitalizations for exacerbations. He is seeing 3 different doctors and has difficulty remembering what medications he is on and often forgets to take his medications

On his clinic visit, he completes a 15-minute health assessment, the SST brief survey version which captures characteristics in Table 3. If he had been unable or unwilling, a provider can complete the 2-minute SST clinician version. Some entries are entered automatically via EMR (e.g., polypharmacy with inconsistent refill requests, multiple medical providers in multiple locations, frequent cycles of hospitalization). He indicates no other complicating features.

1. From the SST based on Table 3, the patient is classified clinically as Global Impression V (Limited reserve and serious exacerbations) due to his dominant condition (heart failure) that leads to exacerbations, and complicating features including a complex web of providers (E2, patient sees more than 1 doctor, from more than 1 site of care), several hospitalizations over a 6-month period for exacerbations of heart failure (I2, 3 or more hospitalizations in the past 6 months), and major polypharmacy (J2, 9 or more prescription medications).

2. The SST uses an algorithm based on evidence and expert opinion to flag potential unmet needs (Table 2). In this case, in addition to universal age- and gender-related screening and vaccination including falls and fracture risk assessment (service function 1), the flags would indicate the potential value of at least a single specialist consultation for recurrent heart failure (service function 2), support coordinating his multiple medical providers (service function 10), monitoring of his heart failure status such as through monitoring of weight and symptoms (service function 5), and medication reconciliation and assistance with adherence (service function 6).

3. The SST flags can serve as an opportunity for the primary care doctor to clarify and make an appropriate referral. But if our patient has numerous flags or otherwise is too complex to have all their needs addressed in the immediate visit, the provider can refer him to a care planner trained for the task, armed with the list of potential means ranging from self-care (as he acknowledges activation in his own care) to other care providers (as he indicates the presence of social support for both medical decisions and basic healthcare services). Importantly, the resulting action/referral includes the function to be fulfilled.

4. As it is simple, the SST could be re-assessment at intervals depending on the patient’s complexity, and at points of transition to more adverse states, and during transfer between providers and settings. If the SST results are incorporated as the patient’s “core” data set maintained in an EMR, characteristics, flags, and associated care plans can be accessed and updated by all providers involved in a patient's care, regardless of setting.

What clinical problems are solved by a simple “needs-based” segmentation approach?

Having worked with numerous health systems, I have regularly observed that the sentiment of integrated population care is stymied by a cacophony of measures, often inconsistent with each other and all inconsistently used within the same organization. This common framework facilitates better communication between providers in different settings, ensuring everyone understands the patient's overall health status and needs. Perhaps most importantly, by de-conflating what we want to do to support our patients’ health from the means, we open ourselves to the healthcare system of the future – one that is flexible and responsive to patient needs.

Focusing on met needs as the health system unit of production has multiple additional benefits:

· It reflects the reality that while we may occasionally be missing the odd need, we are often missing the common needs.

· The definition of needs directly defines success. Success is when the need is met. It is not merely met when a patient with heart failure is weighed. The need is met when the function is fulfilled – that a progressive increase in weight is promptly followed up in a way that can short-circuit an ED visit and hospitalization. In the needs-based framework the prompt follow up is explicitly part of definition of the function (i.e., physiological monitoring and prompt follow up). And when the initial means for fulfilling the function fails to meet the need as intended, this can trigger a revision in the care plan.

· It promotes innovation in meeting needs as functions might be performed by a range of existing options (including, say, family learning wound care), to new technologies such as wound care robots.

· Given the flexibility in selecting means, the approach can improve the likelihood that a solution to meeting needs will be suitable to the patient and their families.

What are administrative benefits?

In addition to these clinical applications, a needs-based measure of production can be used to promote more effective and nimble administrative decision making:

· It can lead to a scoring system to quantify how well needs are being met for each individual and across the population. For instance: Calculate a "Needs Met" score for each individual by summing scores across all relevant needs (0 = Need not addressed; 1 = Need partially addressed; 2 = Need fully addressed).

· The SST can be used to track changes in the population health status over time to assess how well the system is meeting evolving needs as patients move between categories.

o Report scores that are inherently consistent with reality in the clinic can be aggregated at various levels: by SST category, by provider, by clinic, and system-wide.

o Patients can be categorized into groups based on their needs profiles to identify new ways of coordinating addressing needs for patients with common sets of needs. This can incorporate advanced methods of predictive analytics, to target individuals most likely to transition to worse health states.

o The instrument can be used as a global measure of success for developing payment models that incentivize meeting needs across all SST categories, rather than just providing services.

o Resource allocation decision making can be more rational: Use the SST-based needs metric to guide resource allocation, including capitation formulas. Areas with lower "Needs Met" scores may require additional attention or resources.

o Links to quality improvement: Identify patterns in unmet needs within and across SST categories to drive targeted quality improvement initiatives.

If adopted, needs-based segmentation can facilitate system improving research:

· New innovations can be compared in terms of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness analysis of interventions, using randomized controlled trials or quasi-experimental studies to rigorously evaluate the impact of the approach.

· Needs segments can be used to design qualitative studies with focus groups of patients and providers to gather insights on the perceived effectiveness and challenges of the approach.

· The approach itself can be studied for ongoing methods improvement, compare variations of the "meeting needs" approach to traditional service-based models in terms of health outcomes and cost-effectiveness.

· Needs-based segmentation can be subjected to external evaluation by independent researchers or health services research organizations to validate the measurement approach and results. It is suitable for tailoring; the specific measures and methods may need to be adjusted based on data relevant to the local healthcare setting and patient population. The key to tailoring remains unchanged: patient characteristics are indicative of needs, which, defined in functional terms, can be fulfilled by a range of available means that can be monitored and improved leading to progressive improvement in health outcomes and system efficiency.

By implementing such a comprehensive measurement and evaluation system, healthcare organizations can rigorously assess the effectiveness of the "meeting needs" approach. This data-driven method allows for continuous improvement and provides evidence to support broader adoption of the model if a specific innovation proves effective in pilot testing.

Closing remarks: The value of a standard measure of health system production based on met needs

A pragmatic, needs-based segmentation approach, such as the SST, provides a standardized language and framework for understanding and addressing patient needs across all care settings. This shared understanding fosters better communication and collaboration among providers, leading to more integrated and patient-centered care. By shifting our focus from services to solutions, the primary care provider can now be accountable within a healthcare system that is not only effective and efficient but also humane and responsive to the needs of the individuals it serves.

From "Providing Services" to "Meeting Needs"

Medicine has evolved in ways that are both positive (more effective therapies) and negative (impersonal, fragmented, and expensive). This blog discusses a strategy for improving healthcare by reframing our fundamental goal from the traditional "providing services" to a more suitable modern approach: "meeting needs".

The importance of meeting needs may seem self-evident, and one might assume it's already the fundamental goal of healthcare. However, the focus has always been on providing services, which worked well for most of medicine's history.

Historically, a 'patient' (from Latin and Greek roots meaning 'sufferer') sought care for acute problems addressed in one or a few encounters. Providing services effectively met needs. But this conflation is no longer appropriate.

The evolution of medicine presents us with a complex landscape. While we've witnessed remarkable advancements in therapeutic efficacy, we're also grappling with a healthcare system that has become increasingly impersonal, fragmented, and costly. This blog proposes a strategy to address these challenges by reframing our fundamental approach from "providing services" to "meeting needs" – a shift that could significantly improve healthcare delivery.

At first glance, the importance of meeting needs might seem self-evident. One might assume it's already the cornerstone of healthcare. However, historically, the focus has been on providing services, a model that served us well for many years. Traditionally, patients (a term rooted in the concept of "suffering") sought care for acute issues, which were typically addressed in one or a few encounters. In this context, providing services effectively met needs.

However, this conflation of services and needs is no longer appropriate in our current healthcare environment. Policymakers now recognize the broader societal impact of individual health, leading to a more "population-oriented" approach. This expanded view encompasses care for both symptomatic patients and those with asymptomatic chronic conditions such as obesity, diabetes, and frailty.

Moreover, the equation of services with needs has contributed to significant cost inflation. The well-intentioned provision of health insurance often pays for services without explicit links to value. This system incentivizes the provision of more services, particularly those with high profit margins, potentially misaligning service provision with actual patient needs.

On the demand side, we see patients requesting suboptimal services, often due to lack of awareness, misinformation, or influenced by marketing that may not align with their best interests.

I propose a shift in how we measure healthcare system output, particularly at the administrative level. By moving from units of service to units of met needs, using tools for population segmentation based on health and health-related social services, we could potentially alter cost inflation dynamics and promote meaningful innovation.

This approach extends beyond the "value-based healthcare" movement, identifying a key management strategy for implementation. It's also distinct from the potentially over-complex and manipulative "value-based pricing" at the micro-level.

In essence, the traditional equation of services with met needs is no longer sustainable in our modern healthcare landscape. We need a practical metric of met needs to serve as the foundation for organizing and funding healthcare.

In future discussions, we'll explore the root causes of our current dysfunction in using units of service, methods for measuring met needs, and the challenges we face in transitioning to this new metric of healthcare production. While this shift presents significant challenges, it offers the potential for a more effective, efficient, and patient-centered healthcare system.

Primary Care: It’s About Time

Primary care is essential and woefully under-resourced. In Singapore where I spend most of my time, a primary care doc may have no more than 5 minutes per patient. Besides the fact that this may leave no time for anything more than a simple problem, it highlights the need for a model of service that allows primary care to do its essential task: to identify and meet needs in a way that is human and affordable.

It has been estimated that if primary care doctors were to provide all recommended services, it would take more than 24 hours per day. My own primary care doctor in the US stays up to the wee hours reading patient emails, writing notes, checking on test results. Were it not that he has more capacity than the Energizer Bunny, he’d be thoroughly burned out. And many of our best providers are burning out and leaving primary care.

We need a new way.

Which raises the issue of the role of artificial intelligence (AI) in enhancing patient care. While some may fear that AI will ultimately replace physicians – or worse includes trashy applications that waste time – a more nuanced perspective suggests that this technology could serve to augment and empower the frontline clinicians to use their time in a way that is most valuable for patients.

Before considering AI applications that would be useful, consider where a human has a comparative advantage. Humans can intuit and empathize. Humans have 5 coordinated senses. Patients prefer humans.

In this context, the role of AI would be to complement humans by allowing them to do what they are good at, while assuring that needs are identified and addressed, and to improve patient outcomes – all in a reasonable workday.

There are three key ways in which AI can be leveraged to empower physicians and improve patient outcomes.

Rapid access to up-to-date recommendations relevant to the patient at hand

One of the most valuable applications of AI in healthcare is its ability to serve as an intelligent, constantly updating reference tool. With the volume of new medical knowledge growing exponentially, it has become increasingly challenging for individual physicians to maintain comprehensive, real-time familiarity with best practices and the latest treatment modalities.

Consider the example of a primary care physician seeing a patient who noticed a nodule in their neck. The clinician palpates the thyroid and confirms the presence of a nodule. But what’s the current evidence-based recommendations? They go to “Up to Date” – a wonderful resource from the American College of Physicians – which bounces the doctor through multiple hyperlinked entries. After 15 minutes, the doctor is indeed “up to date” but that was a poor use of patient contact time. Not to mention that unlike a lawyer, the doctor can’t charge by the quarter hour for research. Here an AI tool that could perform the task with a single query and the doctor can do a more in-depth search in time set aside for education (and they can get continuing medical education credits to boot.)

Streamlining Administrative Tasks

Physicians often find themselves burdened by a range of administrative responsibilities that do not directly contribute to patient care, such as documentation, order entry, and prior authorization processes. While these tasks are necessary, they can detract from the time available for meaningful interactions with patients.

AI can be leveraged to automate many of these repetitive, time-consuming administrative functions. By offloading these responsibilities to intelligent software systems, physicians can reclaim valuable time to focus on personalized care delivery, patient education, and care coordination. This has the potential to improve both physician and patient satisfaction, as the clinical encounter can be centered on the unique needs and concerns of the individual.

A prime example of this type of AI-driven administrative automation is the use of natural language processing (NLP) to streamline clinical documentation. Rather than manually typing notes, physicians could simply dictate their observations and recommendations, with the AI system automatically translating the audio into a formatted, structured clinical note. This not only saves time, but also ensures greater accuracy and completeness of the medical record.

Similarly, AI can be leveraged to handle the bane of existence in a doctors life (at least in the US), complex prior authorization process, which requires physicians to obtain approval from insurance providers before prescribing certain medications or ordering specific tests or procedures. An AI system could autonomously interface with payer portals, submit the necessary documentation, and track the status of authorization requests. This would spare the physician from having to navigate these bureaucratic hurdles, freeing them up to focus on direct patient care.

Ensuring Comprehensive, Holistic Care

Even the most diligent and experienced physicians can sometimes overlook or fail to fully consider important details about a patient's overall health and social circumstances. The fast pace of a typical clinic visit, combined with the sheer volume of information that must be processed, makes it easy for crucial contextual factors to slip through the cracks.

AI systems could ask a limited number of focused questions to identify flags needing further discussion. Or perhaps, with their ability to rapidly synthesize large amounts of data, can help ensure that the full scope of a patient's needs are identified and addressed. By drawing from the patient's complete medical record, as well as other relevant sources, an AI assistant could surface important details that the physician may have missed - such as medication interactions, social determinants of health, or psychosocial barriers to care. This would support a more holistic, patient-centered approach to treatment planning and care management.

Consider a hypothetical scenario where an elderly patient visits their primary care physician for a routine checkup. During the visit, the physician notes that the patient's blood pressure is elevated and adjusts their medication accordingly. However, an AI system integrated into the electronic health records detects multiple providers prescribing additional and potentially conflicting medications. The doctor asks how the patient is able to coordinate across all these providers and learns that the patient has recently experienced a significant life event, such as the loss of a spouse. The physician can now spend the time saved from research, note writing, and calls to insurers to explore ways to coordinate amongst providers, and to identify strategies to support the patient through their stressful loss.

Can AI use the electronic health record to ensure that the patient's full range of health and social needs are identified and addressed, beyond the immediate presenting concerns? Until we have better electronic records, this is likely a “no”.

The Impact of AI on the Future of Healthcare

Ultimately, the strategic integration of AI into the healthcare system has the potential to empower physicians, enhance the patient experience, and drive improved outcomes. Rather than fearing AI as a replacement for human clinicians, we should embrace those applications that augment and support the tireless efforts of those on the frontlines of medicine.

As AI continues to advance, applications in healthcare should be considered if they are demonstrably valuable. One can envision a future where clinicians are seamlessly supported by intelligent software assistants that handle the administrative burden, provide real-time access to the latest medical knowledge, and surface critical insights to inform personalized care plans.

This AI-powered approach could yield a wide range of benefits, including:

Improved clinical decision-making and patient safety, by ensuring adherence to evidence-based guidelines and catching potential errors or oversights

Enhanced patient engagement and satisfaction, as physicians can devote more time to listening, educating, and collaborating with their patients

Better care coordination and continuity, as AI systems maintain a comprehensive, longitudinal understanding of each patient's health status and needs

Reduced clinician burnout, by alleviating the administrative workload and cognitive burden that often contribute to stress and job dissatisfaction among healthcare providers

Of course, the successful integration of AI in healthcare will require careful consideration of important issues such as data privacy, algorithmic bias, and the appropriate role of human oversight. But when implemented thoughtfully and with robust safeguards in place, the potential benefits of AI-augmented care could be immense.

Rather than fearing AI as a replacement for human clinicians, we should embrace it to the extent it elevates the practice of medicine. This means that there must be a strong form of governance over the introduction of new applications that indeed ensure that every patient encounter is grounded in the latest knowledge, tailored to individual needs, and focused on delivering the highest standard of compassionate, holistic care.